Closure? I Hardly Know Her!

1396 words. Time to Read: About 13 minutes.Cover image credit: this amazing StackOverflow answer.

I’ve learned about closures a few different times, and each time, I’ve come away feeling like I get it, but I don’t necessarily understand why people make such a big deal out of them. Yeah, hooray, you get functions that can persist their data! I’ve seen people post things like, “If you’re not using closures, you’re really missing out.” I think I’ve finally figured out why people are so excited, and why I was confused. This post will explain what closures are, when you might want to use them, and why it took me so long to get why they’re special.

What are Closures

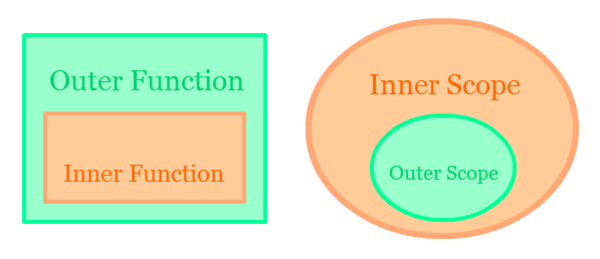

A closure (also called a function closure or a lexical closure) is when you find a way of wrapping up a function with the state in which it was defined into one connected and persistent bundle. I’ll show you a bunch of examples if that doesn’t make sense. There’s a number of ways to create a closure, but the canonical one is to define and return a function from within another function. Here’s what I mean.

def build_zoo():

animals = []

def add_animal(animal):

animals.append(animal)

return animals

return add_animal

zoo_a = build_zoo()

zoo_b = build_zoo()

zoo_a("zebra")

# => ["zebra"]

zoo_a("monkey")

# => ["zebra", "monkey"]

zoo_b("snek")

# => ["snek"]

zoo_a("panda")

# => ["zebra", "monkey", "panda"]

Thanks to @Doshirae and Nicholas Lee for pointing out a typo in the return statement!

The build_zoo function is a kind of “factory” that creates a scope and defines a function within that scope. Then it gives the function that still has access to that scope (and the variables therein) to you. After the build_zoo function ends, it keeps the stack frame and variables defined (like animals) available to the returned add_animal function, for later reference. And every time you call this build_zoo function, it creates a brand new scope, unconnected to any of the other scopes. That’s why zoo_a and zoo_b were not able to affect each other when they were called!

Side Note: Python and Scopes

In Python, you are unable to modify variables outside your scope without extra work. So, if you tried something like this:

def build_incrementer():

current_value = 0

def increment():

current_value += 1

return current_value

return increment

incrementer = build_incrementer()

incrementer()

# => UnboundLocalError: local variable 'current_value' referenced before assignment

You get an error! This is not so in many languages. In many languages, it’s ok to access variables in parent scopes. In Python, you’ll have to do this:

def build_incrementer():

current_value = 0

def increment():

nonlocal current_value # <==

current_value += 1

return current_value

return increment

This lets you reach out and modify this value. You could also use global, but we’re not animals, so we won’t.

OK, but So What?

“You can keep track of state like a billion different ways!” you say exaggeratingly. “What’s so special about closures? They seem unnecessarily complicated.” And that’s a little bit true. Generally, if I wanted to keep track of my state with a function, I would do it in one of a few different ways.

Generator Functions

def build_incrementer():

current_value = 0

while True:

current_value += 1

yield current_value

inc_a = build_incrementer()

inc_b = build_incrementer()

next(inc_a)

# => 1

next(inc_a)

# => 2

next(inc_a)

# => 3

next(inc_b)

# => 1

This method is very “Pythonic”. It has no inner functions (that you know of), has a reasonably easy-to-discern flow-path, and (provided you understand generators), and gets the job done.

Build an Object

class Incrementer:

def __init__(self):

self.value = 0

def increment(self):

self.value += 1

return self.value

# Or, just so we can match the section above:

def __next__(self):

return self.increment()

inc_a = Incrementer()

inc_b = Incrementer()

next(inc_a)

# => 1

next(inc_a)

# => 2

next(inc_b)

# => 1

This is another good option, and one that also makes a lot of sense to me coming, having done a good amount of Ruby as well as Python.

Global Variables

current_value = 0

def increment():

global current_value

current_value += 1

return current_value

increment()

# => 1

increment()

# => 2

increment()

# => 3

No.

But, I–

No.

Wait! Just let me–

Nope. Don’t do it.

Global variables will work in very simple situations, but it’s an really quick and easy way to shoot yourself in the foot when things get more complicated. You’ll have seventeen different unconnected functions that all affect this one variable. And, if that variable isn’t incredibly well named, it quickly becomes confusion and nonsense. And, if you made one, you probably made twenty, and now no-one but you knows what your code does.

Why Closures are Cool

Closures are exciting for three reasons: they’re pretty small, they’re pretty fast, and they’re pretty available.

They’re Small

Let’s look at the rough memory usage of each method (except global variables) above:

import sys

def build_function_incrementer():

# ...

funky = build_function_incrementer()

def build_generator_incrementer():

# ...

jenny = build_generator_incrementer()

class Incrementer:

# ...

classy = Incrementer()

### Functional Closure

sys.getsizeof(build_function_incrementer) # The factory

# => 136

sys.getsizeof(funky) # The individual closure

# => 136

### Generator Function

sys.getsizeof(build_generator_incrementer) # The factory

# => 136

sys.getsizeof(jenny) # The individual generator

# => 88

### Class

sys.getsizeof(Incrementer) # The factory (class)

# => 1056

sys.getsizeof(classy) # The instance

# => 56

Surprisingly, the generator function’s output actually ends up being the smallest. But both the generator function, and the traditional closure are much smaller than creating a class.

They’re Fast

Let’s see how they stack up, time-wise. Keep in mind, I’m going to use timeit because it’s easy, but it won’t be perfect. Also, I’m doing this from my slowish little laptop.

import timeit

### Functional Closure

timeit.timeit("""

def build_function_incrementer():

# ...

funky = build_function_incrementer()

for _ in range(1000):

funky()

""", number=1)

# => 0.0003780449624173343

### Generator Function

timeit.timeit("""

def build_generator_incrementer():

# ...

jenny = build_generator_incrementer()

for _ in range(1000):

next(jenny)

""", number=1)

# => 0.0004897500039078295

### Class

timeit.timeit("""

class Incrementer:

def __init__(self):

self.value = 0

def increment(self):

self.value += 1

return self.value

def __next__(self):

return self.increment()

classy = Incrementer()

for _ in range(1000):

next(classy)

""", number=1)

# => 0.001482799998484552

Once again, the class method comes in at the bottom, but this time we see a marginal speed bump with the functional closure. However, keep in mind, the final argument for closures is the strongest one.

They’re Available

This is the one that took me the longest to find out. Not all languages are as lucky as Python. (Excuse me while I prepare my inbox for a deluge of hate mail.) In Python, we are lucky enough to have Generators as well as a number of ways to create them, like Generator functions. Honestly, if I had to choose from the above methods, and I was writing Python, I’d actually recommend the Generator Function method, since it’s easier to read and reason about.

However, there are a lot of languages that aren’t as “batteries included.” This can actually be a benefit if you want a small application size, or if you’re constrained somehow. In these cases, as long as your language supports creating functions, you should be able to get all the benefits of Generators (lazy evaluation, memoization, the ability to iterate through a possibly infinite series…) without any fancy features.

In JavaScript, you can now use a version of generators, but that’s ES6 functionality that hasn’t always been there. As far as I can tell, this isn’t a built-in functionality in Go either (although some research shows that it might be more idiomatic to use channels instead). I’m sure there are many other lower-level languages as well where a simple function closure is easier than trying to write your own Generator.

Share Your Wisdom!

Since I don’t have a whole lot of experience with low-level languages, the pros and cons of closures are new to me. If you have some better explanations or any examples of when a closure is the perfect tool for the job, please let me know about it and I’ll do my best to broadcast your wisdom.

Author: Ryan Palo | Tags: python functional | Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee

Like my stuff? Have questions or feedback for me? Want to mentor me or get my help with something? Get in touch! To stay updated, subscribe via RSS